Robert Bass Dickens Dream. Charles Dickens London House

“My uncle was lying with half-closed eyes, his nightcap had slipped down to his very nose. His thoughts were already beginning to get confused, and instead of the situation surrounding him, the crater of Vesuvius appeared in front of him, the French Opera, the Colosseum, Dolly's London tavern, all that hodgepodge of sights different countries like a traveler's head is stuffed. In short, he went to sleep.

So writes the marvelous writer Washington Irving in his Traveler's Tales. But I recently happened to lie not with half-closed, but with wide open eyes; and the nightcap didn't slide down on my nose, because for hygienic reasons I never put on a nightcap, but my hair was tangled and scattered over the pillow; and besides, I did not go to sleep at all, but stubbornly, obstinately and furiously kept awake. Perhaps unintentionally and without asking any scientific purposes, I nevertheless confirmed by example the theory of split consciousness; perhaps one part of my brain, awake, was watching the other, falling asleep. Be that as it may, something in me, more than anything in the world, longed to sleep, and something else did not want to fall asleep, showing a stubbornness truly worthy of George the Third.

Thinking about George the Third - I devote this essay to my thoughts during insomnia, since most people have insomnia, and therefore this subject should interest them - I thought of Benjamin Franklin, and after that his essay on the art of causing pleasant dreaming, which, it would seem, should include the art of falling asleep. And since I have read this essay many times in early childhood and I remember everything I read then, just as vividly as I forget everything I read now, I mentally quoted: “Get out of bed, fluff and turn the pillow, well, at least twenty times, shake the sheets and the blanket; then open the bed and let it cool, meanwhile, without getting dressed, walk around the room. When you feel that the cold air is unpleasant for you, lie down again in bed, and you will soon fall asleep, and your sleep will be strong and sweet. No matter how! I did everything exactly as prescribed, and only succeeded in opening my eyes, if possible, even wider.

And then there was Niagara. Perhaps I remembered her by association - quotes from Irving and Franklin directed my thoughts in an American direction; yes, I stood on the edge of the waterfall, it roared and fell at my feet, and even the rainbow that played on the spray when I last time I saw him in reality, again pleased my eyes. However, I could see my night-light just as clearly, and as the dream seemed to be thousands of miles farther from me than Niagara, I decided to think a little about the dream. As soon as I decided this, I found myself, God knows how, in the theater of Drury Lane, saw a wonderful actor and close friend of mine (whom I remembered that day) in the role of Macbeth and heard his voice praising the "healing balm of a sick soul" . as I have heard over the years.

So sleep. I will force myself to think about sleep. I firmly resolved (I continued mentally) to think about sleep. We must hold on to the word “sleep” as tightly as possible, otherwise I will be carried somewhere again. Well, of course, I already feel like I'm rushing for some reason to the slums of Claire Market. Dream. It would be interesting, in order to verify the opinion that sleep equalizes everyone, to find out whether the same dreams are visited by people of all classes and ranks, rich and poor, educated and ignorant. Here, for example, Her Majesty Queen Victoria is sleeping in her palace tonight, and here, in one of Her Majesty's prisons, Charlie Morgun, an inveterate thief and a vagabond, is sleeping. Her Majesty has fallen hundreds of times in her sleep from the same tower from which I feel entitled to fall from time to time. Charlie Morgun too. Her Majesty opened the session of Parliament and received foreign ambassadors, dressed in more than scanty clothes, of which the insufficiency and inappropriateness plunged her into great embarrassment. I, for my part, have suffered unspeakable agony in presiding over a banquet in a London tavern in my underwear, and my good friend Mr. Bate, with all his courtesy, could not convince me that this outfit was the most suitable for the occasion. Charlie Morgun appeared before the court over and over again, and not in this form. Her Majesty is well acquainted with a certain vault, or canopy, with an incomprehensible pattern, vaguely resembling eyes, which sometimes disturbs her sleep. He is also familiar to me. Meet Charlie. All three of us had to glide with inaudible steps through the air, above the ground itself; and have engaging conversations with different people knowing that all these people are ourselves; and rack our brains, wondering what they will tell us; and unspeakably marvel at the secrets that they revealed to us. Probably all three of us committed murders and hid corpses. There is no doubt that we all at times desperately wanted to scream, but the voice betrayed us; that we went to the theater and could not get into it; that we dream of youth much more often than later years; that we ... no, I forgot! The thread has broken. And so I rise. I am lying in bed, a night light is burning nearby, and I, for no reason and already without any visible connection with my previous thoughts, climb Great St. Bernard! I lived in Switzerland, wandered a lot in the mountains, but why I was drawn there now, and why exactly to St. Bernard, and not to some other mountain, I have no idea. Lying awake - all my senses are sharpened to the point that I distinguish distant sounds, inaudible at other times - I make this path, as I once did it in reality, on the same summer day, in the same cheerful company (two with since then, alas, have died!), and the same path leads uphill, the same black wooden hands show the way, the same come across here and there shelters for travelers; the same snow falls on the pass, and the same frosty fog there, and the same frozen monastery with the smell of a menagerie, and the same breed of dogs, now dying out, and the same breed of hospitable young monks (it’s sad to know that they are all crooks!) , and the same hall for travelers, with a piano and evening conversations by the fire, and the same supper, and the same lonely night in the cell, and the same bright, fresh morning, when, inhaling rarefied air, it is as if you are plunging into an ice bath! Well, have you seen a new miracle? And why did it get into my head in Switzerland, on a mountain peak?

It is a chalk drawing which I once saw in semi-darkness on a door in a narrow alley near the village church—the first church I was taken to. How old I was then - I don’t remember, but this drawing frightened me so much - probably because there was a cemetery nearby, the man himself in the drawing smokes a pipe and he is wearing a wide-brimmed hat, from under which his ears stick out horizontally, and in general there is nothing terrible in it, except for the mouth to the ears, bulging eyes, and hands in the form of bunches of carrots, five pieces in each - which still makes me feel terrible when I remember (and I recalled this more than once during insomnia), how I ran home and kept looking around, and felt with horror that he was chasing me - whether he got off the door, or together with the door, I don’t know and probably never knew. No, again my thoughts went somewhere else. You can't let them run like that.

Flights to hot-air balloon in the past season. They are perhaps suitable to pass the hours of insomnia. I just have to hold them tight, otherwise I already feel that they are slipping away, and instead of them, the Mannings, husband and wife, hang over the gates of the prison on Horsmonger Lane. This depressing picture reminded me of what a trick my imagination once played on me: having witnessed the execution of the Mannings and leaving the place of execution, when both bodies were still hanging over the gate (the man is a saggy dress, as if there is no longer a person under him; the woman is a beautiful figure, so carefully pulled into a corset and so skillfully dressed that even now, slowly swaying from side to side, she looked neat and smart), then for several weeks I could not imagine the external appearance of the prison by any means (and the shock that I experienced, again and again brought my thoughts back to her) without imagining the two corpses still hanging in the morning air. It was only after I passed this gloomy place late at night, when the street was quiet and deserted, and saw with my own eyes that there were no corpses there, that my imagination agreed, so to speak, to take them out of the noose and bury them in the prison yard, where they have been dormant ever since.

"That's all"? These words seemed to me a too restrained conclusion to the story of how Miss Winter lost her mother. Of course, she had a low opinion of Isabella's maternal qualities, and the very word "mother" was alien to her vocabulary. It is not surprising: from what has been said, it was clear that Isabella did not have any parental feelings for her daughters. However, who am I to judge the relationship of other people with their mothers?

Closing my notepad, I got up from my chair.

“I'll be back in three days, which is Thursday,” I reminded her.

And she left, leaving Miss Winter alone with her black wolf.

DICKENS' OFFICE

I'm done with my nightly entries. All my twelve pencils are blunt; it was time to clean them up. One by one, I inserted the pencils into the sharpening machine. If you turn its handle slowly and smoothly, you can get writhing chips from the edge of the table to the very bottom of the wastebasket, but today I was too tired, and the chips broke off every now and then on weight.

I thought about the story and its characters. I liked the Missus and John the digger. Charlie and Isabella were annoying. The doctor and his wife certainly had noble motives, but I suspected that their meddling in the fate of the twins would not lead to anything good.

As for the twins, then I was at a loss. I could judge them only from the words of third parties. John the digger thought they couldn't talk properly; The missus was sure that they did not perceive other people as full-fledged living beings; the villagers thought they were crazy. With all that, I, oddly enough, did not know the opinion of the narrator herself about them. Miss Winter was like a source of light, illuminating everything but herself. She was the black hole at the heart of the story. She spoke of her characters in the third person, and only in the last episode did she use the pronoun "we", while the pronoun "I" has not yet been used even once.

If I asked her about it, it was not difficult to predict the answer: "Miss Li, we have an agreement with you." I had asked her questions before, clarifying some details of the story, and although at times she deigned to comment, more often there was a reminder of our first meeting: “No cheating. No jump ahead. No questions."

Therefore, I resigned myself to the fact that I would have to guess for a long time; however, on the same evening, events occurred that somewhat clarified the situation.

I had tidied up my desk and was packing my suitcase when there was a knock at the door. I opened it and saw Judith in front of me.

“Miss Winter asked if you could give her a few minutes right now?” “I had no doubt that it was a polite translation of a much shorter command: “Bring Miss Lee here,” or something of the sort.

I folded my last blouse, put it in my suitcase, and headed off to the library.

Miss Winter sat in her usual place, lit by the flames of the fireplace, while the rest of the library was plunged into darkness.

- Turn on the light? I asked from the door.

"No," came a voice from the far end of the room, and I made my way there along the dark passageway between the cabinets.

The shutters were open and the mirrors reflected the star-studded night sky.

When I got to Miss Winter, I found her deep in thought. Then I sat down on a chair and began to observe the reflection of the stars in the mirrors. So half an hour passed; Miss Winter thought, and I silently waited.

Finally she spoke:

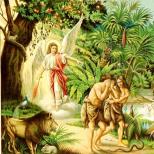

Have you ever seen a picture of Dickens in his office? The artist's name seems to be Basho*. I must have a reproduction somewhere, I'll find it for you later. Dickens is dozing in an armchair pulled away from the table; his eyes are closed, his bearded head is bowed to his chest. On his feet are his slippers. And around him, like cigar smoke, the characters of his books hover: some circle over the pages of a manuscript opened on the table, others hover behind him, and others descend, as if they expect to walk on the floor, like living people. Why not? They are written in the same clear lines as the author himself, so why shouldn't they be just as real? In any case, they are more real than the books on the shelves, which the artist has marked only with careless, ghostly strokes.

>> * This refers to the picture of the English artist Robert W. Bass "Dickens' Dream", written shortly after the death of the writer in 1870.

Why am I remembering this now, you ask? This picture can serve as an illustration of how I spent most own life. I locked myself away from the outside world in my office, where only the heroes created by my imagination kept me company. For almost sixty years, I eavesdropped on the conversations of these non-existent people with impunity. I shamelessly peered into their souls, into their bedrooms and water closets. I followed every movement of their pens as they wrote Love letters and wills. I have watched lovers in the moments they make love, murderers in the act of killing, children in their secret games. The doors of prisons and brothels were flung open before me; sailing ships and camel caravans carried me across seas and deserts; centuries and continents changed at my whim. I saw the spiritual insignificance of the greats of this world and the nobility of the orphans and the poor. I bent so low over the beds of the sleepers that they could feel my breath on their faces. I saw their dreams.

My office was filled with characters waiting for me to write about them. All these imaginary people were eager to enter into life, they insistently tugged at my sleeve and shouted: “I'm next! Now it's my turn!" I had to make a choice. And when it was done, the rest fell silent for a dozen months or a year, until I finished another story, and then the same turmoil rose again.

And every time, over the years, when I looked up from the page, finishing the story, or contemplating the death scene, or just picking right word, I saw the same face behind this crowd. A well known face. White skin, reddish hair, bright green eyes staring at me. I knew perfectly well who it was, but nevertheless I always shuddered in surprise when I saw her. She managed to take me by surprise. Sometimes she opened her mouth and tried to tell me something, but she was too far away, and in all these years I never heard her voice. I myself was in a hurry to be distracted by something else with such a look as if I did not notice it at all. Though I don't think I was able to fool her with that trick.

People are surprised by my performance. It's all about this girl. I was forced to start a new book five minutes after the end of the previous one only because I was afraid to take my eyes off the desk, because then I would certainly meet her eyes.

Years passed; the number of my books on the store shelves grew, and the number of characters that inhabited my office decreased accordingly. With each new book, the chorus of voices in my head became quieter. The imaginary people who wanted my attention disappeared one by one, and behind this thinning group, moving closer with each book, there was invariably her. Green-eyed girl. She waited.

And then the day came when I finished the manuscript of my last book. I wrote the final phrase and put an end to it. I knew what would happen next. The pen slipped from my hand and my eyes closed.

“Well, that's all,” I heard her (or my own?) voice. “Now we are alone.”

I tried to argue with her.

“This story won’t work for me,” I said. - It happened so long ago, I was still a child then. I forgot everything".

But my excuses didn't work.

“But I didn’t forget anything,” she said. “Remember how…”

It is useless to resist the inevitable. I remembered everything.

But that's not the point. I mean, the book is excellent, although to me personally it does not at all resemble English Gothic (they say that it is a glorified representative of such a genre as Neo-Gothic), but rather something similar to Andahazi and McCormick. Well, plus English flavor, of course, yes, but just flavor. It's not about that.

And the fact is that in this book I came across a mention of one painting by the artist Robert William Bass called "Dickens' Dream". And I liked her description so much that I immediately got into Google (oh, blessed Internet) to look at her.

And the picture was brilliant. The very idea, and execution, and even her story is as mysteriously gloomy as the object of the image.

When I got to Miss Winter, I found her deep in thought. Then I sat down on a chair and began to observe the reflection of the stars in the mirrors. So half an hour passed; Miss Winter thought, and I silently waited.Finally she spoke:

Have you ever seen a painting of Dickens in his office? The artist's name seems to be Basho*. I must have a reproduction somewhere, I'll find it for you later. Dickens is dozing in an armchair pulled away from the table; his eyes are closed, his bearded head is bowed to his chest. On his feet are his slippers. And around him, like cigar smoke, the characters of his books hover: some circle over the pages of a manuscript opened on the table, others hover behind him, and others descend, as if they expect to walk on the floor, like living people. Why not? They are written in the same clear lines as the author himself, so why shouldn't they be just as real? In any case, they are more real than the books on the shelves, which the artist has marked only with careless, ghostly strokes.

Here is the picture.

I read on the Internet that the artist was a big fan of Dickens' work and was even once invited by a publishing house to illustrate one of his works. However, the publishers did not like the illustrations presented and they turned to someone else. This unpleasant event, however, did not affect the enthusiastic attitude of Bass to the books of Dickens.

The picture that attracted me so much (and not only me, in general, although this, of course, is not so important anymore;)), Bass began to write after the death of Dickens. He, too, soon died, and, as far as I understood, the picture was not quite finished. However, I did not carefully read the explanations for this picture on one of the pages on the Internet dedicated to Dickens, so I could have confused something. I was more attracted to the picture itself - its plot and details. Unfortunately, I didn’t find it on a larger scale, it’s a pity, I would like to see the details in more detail.

By the way, I don’t know, maybe something else will be connected further with this picture in the book that I am reading. So far, about a quarter of the total volume has been read :) It is easy and fascinating to read, the plot is tricky and mystical, but I don’t even like it more, but such small details, such as, for example, a description of the recording technique used by the main heroine-biographer (I even think to adopt); reflections on the topic of the relevance of truth and fiction in certain situations and in general in principle; the idea of books and the stories told in them (or by them?) as a kind of living creatures with their own characters.

The house in London where Charles Dickens lived

The Charles Dickens Museum is located in Holborn, London. It is located in the only house that has survived to this day, where the writer Charles Dickens and his wife Catherine once lived. They moved here in April 1837, a year after their marriage, and lived there until December 1839. There were three children in the family, a little later two more daughters were born. In total, the Dickens had ten children. As the family grew, the Dickens moved to larger apartments.

It is here in the very early XIX century Dickens created Oliver Twist and Nicholas Nickleby.

The museum contains exhibits that tell both about the Dickensian era as a whole, and about his writing career, about the works and heroes of the writer, about his personal and family life. In 1923, Dickens' house on Doughty Street was under threat of demolition, but was bought out by the Dickens Society, which had already existed for over twenty years. The building was renovated, and in 1925 the house-museum of Charles Dickens was opened here.

**************************************** **************************************** *******************

Katherine Dickens - writer's wife

They married in the spring of 1836. The honeymoon of 20-year-old Katherine and 24-year-old Charles lasted only a week: in London, obligations to publishers awaited him.

The first years of marriage with the Dickens couple lived Mary, Catherine's younger sister. Dickens adored her, lively, cheerful, spontaneous. She reminded Charles of his sister Fanny, with whom the most precious childhood memories were associated. Her innocence made the writer feel the guilt inherent in Victorian men ... But he curbed his natural passion in every possible way. It is unlikely that Katherine liked such coexistence, but she did not have the habit of making scenes for her husband. One day, the three of them returned from the theater, and Mary suddenly lost consciousness. From that moment on, Charles did not let the girl out of his arms, and her last words meant only for him. She died of a heart attack. On the tombstone, he ordered to engrave the words “Young. Beautiful. Good." And he asked his relatives to bury him in Mary's grave.

**************************************** ***************************************

The Dickens Society, which existed by that time for more than 20 years, managed to buy this building, where the Charles Dickens Museum was organized. About him for a long time only experts knew, and students of literary faculties. However, interest in the work of the writer in recent times began to grow strongly, and on the eve of its 200th anniversary, a lot of money was invested in the renovation and restoration of the museum. large sums. The updated and restored museum opened just a month after the start of work - December 10, 2012.

The restorers have tried to recreate the true atmosphere of the Dickensian house. Here, all the furnishings and many things are authentic and once belonged to the writer. According to the museum staff, the specialists did everything to make the visitor feel that the writer was only away for a short while and will return soon.

They tried to recreate the Charles Dickens Museum as a typical English dwelling of a middle-class family of the 19th century, although Dickens himself was always afraid of poverty. The kitchen has been restored here with all the attributes, a bedroom with a luxurious bed and a canopy, a cozy living room, a dining room with plates on the table.

Portrait of young Charles

Portrait of Charles Dickens by Samuel Drummond These Victorian-style plates feature portraits of Dickens himself and his friends. On the second floor is his studio, where he created, his wardrobe, his desk and chair, shaving kit, some manuscripts and first editions of his books are carefully preserved. There are also paintings, portraits of the writer, personal items, letters.

"Shadow" Dickens on the wall of the hall, as it were, invites you to look at the office, dining room, bedrooms, living room, kitchen.

0" height="800" src="https://img-fotki.yandex.ru/get/9823/202559433.20/0_10d67f_5dd06563_-1-XL.jpg" style="border: 0px none; margin: 5px;" width="600">

Writer's office

Catherine Dickens room

Interior of Catherine Dickens' Room

Katherine and Charles

Bust of Katherine

Portrait of Katherine with sewing

Under the portrait in the window is the same sewing made by her hands... But the shot turned out not sharp... She was three years younger than him, pretty, with blue eyes and heavy eyelids, fresh, plump, kind and devoted. He loved and appreciated her family. Though Katherine didn't stir up the passion in him that Maria Bidnel did, she seemed to be the perfect match for him. Dickens intended to make himself known loudly. He knew that he would have to work long and hard, and he liked to do everything quickly. He wanted to have a wife and children. He had a passionate nature and, having chosen a life partner, he sincerely became attached to her. They became one. She was "his better half”, “wife”, “Mrs. D.” - in the early years of their marriage, he called Katherine only that and spoke of her with unbridled delight. He was definitely proud of her, as well as the fact that he managed to get such a worthy companion as his wife.

Salon-studio where Dickens read his works

The needs of Dickens family members exceeded his income. A disorderly, purely bohemian nature did not allow him to bring any order into his affairs. He not only overworked his rich and fruitful brain, forcing it to overwork creatively, but being an unusually brilliant reader, he tried to earn decent fees by lecturing and reading passages from his novels. The impression of this purely acting reading was always colossal. Apparently, Dickens was one of the greatest reading virtuosos. But on his trips he fell into the hands of some dubious entrepreneurs and, while earning, at the same time brought himself to exhaustion.

Second floor - studio and private office

On the second floor there is his studio where he worked, his wardrobe, his desk and chair, shaving kit, some manuscripts and first editions of his books are carefully preserved. There are also paintings, portraits of the writer, personal items, letters.

Victorian era painting

Dickens armchair

Famous portrait in a red chair

Dickens' personal desk and manuscript pages...

Dickens and his immortal heroes

The museum houses a portrait of the writer, known as "Dickens' Dream", painted by R.W. Bass (R.W. Buss), illustrator of Dickens' book The Posthumous Papers of the Pickwick Club. This unfinished portrait depicts the writer in his office, surrounded by the many characters he created.

Mary's young sister-in-law's bedroom

In this apartment, Dickens suffered the first serious grief. There, his wife's younger sister, seventeen-year-old Mary Gogard, died almost suddenly. It is difficult to imagine that the novelist, who had married for love only a year and a half earlier, felt a passion for a young girl, almost a child, who lived in his house, but it is certain that he was united with her by more than brotherly affection. Her death so struck him that he abandoned all his literary works and left London for a few years. He kept the memory of Mary throughout his life. Her image stood before him when he created Nelly in the Antiquities Shop; in Italy he saw her in his dreams, in America he thought of her in the noise of Niagara. She seemed to him the ideal of feminine charm, innocent purity, a delicate, half-blown flower, mowed too early by the cold hand of death.

Bust and original documents

Charles' dress suit

Authentic lamp in Mary's room

canopy bed...

English translator...)))

The guide to the museum was given out for a while and only for English language Therefore, we are very grateful to Olga for her invaluable help...)))

Bureau for papers with documents...

Medical devices...

Dickens' favorite chair...

Exhibition room of quotes and sayings...

The Museum organized an exhibition "Dickens and London", dedicated to the 200th anniversary of the birth of the great English writer. Under the roof and in the side rooms of the building there are interesting installations.

Bust of Father Dickens

Dickensian London

Portraits of Dickens children and their clothes

Catherine was a very persistent woman, she never complained to her husband, did not shift family concerns to him, but her postpartum depression and headaches irritated Charles more and more, who did not want to recognize the validity of his wife's suffering. Home idyll, born of his imagination, did not correspond to reality. The desire to become a respectable family man went against his nature. I had to suppress a lot in myself, which only exacerbated the feeling of dissatisfaction.

With children, Charles also showed the duality characteristic of his nature. He was gentle and helpful, entertained and encouraged, delved into all the problems, and then suddenly cooled off. Especially when they reached the age when his own serene childhood ended. He felt the constant need to take care, first of all, that the children would never experience the humiliations that fell to his lot. But at the same time, this concern was too burdensome for him and prevented him from continuing to be a passionate and tender father.

After 7 years of marriage, Dickens increasingly began to flirt with women. Katherine's first open rebellion about this struck him to the core. Having grown fat, with faded eyes, barely recovering from another birth, she sobbed muffledly and demanded that he immediately stop his visits to the “other woman”. The scandal erupted because of the friendship of Dickens in Genoa with the Englishwoman Augusta de la Rua.

A complete break with Catherine occurred after Charles began to show signs of attention to her younger sister Georgia.

The writer published in his weekly "Home Reading" a letter, called "angry". Until now, the public did not suspect anything about the events in the writer's personal life, now he told everything himself. The main theses of this message are as follows: Katherine herself is to blame for their break with his wife, it was she who turned out to be unsuitable for family life with him, for the role of wife and mother. Georgina is what kept him from breaking up. She also raised children, since Katherine, according to her husband, was a useless mother (“Daughters turned into stones in her presence”). Dickens did not lie - his feelings for women were always distinguished by a special either negative or positive intensity.

All their actions, which they committed from the moment he rewarded them with a negative "image", only confirmed in his mind that they were right. So it was with my mother, and now with Katherine. Much of the letter was dedicated to Georgina and her innocence. He also admitted to the existence of a woman, for whom he "experiences a strong feeling." With his public confession, which, after a long habit of keeping his spiritual secrets, became extreme in its form and content, he seemed to win another "battle with life." Won the right to break with the past. Almost all friends turned their backs on the writer, taking the side of Katherine. This he did not forgive them until the end of his life. At the same time, he composed another letter to refute the storm of gossip and rumors that had risen. But most newspapers and magazines refused to publish it.